Following Jim Chalmer’s third Federal Budget as Treasurer, those of us who live and breath macroeconomics have been sifting through the granular detail of the country's biggest accounting exercise.

While I’m usually most focused on the policy areas that I’m most passionate about, namely industry policy, skills formation, job creation and employment services; this year I find myself zeroing in on inflation.

While inflation is an incredibly critical measure of the economy, it’s not inflation itself that’s keeping me up. What I’m concerned about is how poorly it is being covered by economic commentators within mainstream media.

The vast majority of coverage has demonstrated a shockingly low level of economic literacy, which I find both baffling and infuriating in equal measure.

It’s baffling because the issues with the coverage are based on information that is taught in first year economics, and it’s infuriating because it means that we’re collectively drawing incorrect conclusions about what we need to do to combat it.

If you open a newspaper, scroll through a media app or turn on the tv, you’ll find that every piece covering the will make at least two, and usually all three, of these points:

Inflation is dangerous high;

Any increase in demand (e.g higher wages and increase spending) will drive inflation; and

We need to show fiscal restraint to curb inflation.

While we’re right to look at ways to control inflation, the collective understanding of what inflation is, what is causing it and what we should do about it, suffers from various fallacies which are caused by a lack of economic literacy amongst the commentariat.

In this essay, I want to go through these arguments and highlight the fallacies. I want to show you not just how they’re not only wrong, but also why the solutions drawn from these arguments are actually incapable of reducing inflation - and I want to discuss what we should be doing instead.

Inflation is Dangerously High

Starting with inflation levels, there’s no doubt that prices are increasing, that inflation is higher than we traditionally feel comfortable with, and that the vast majority of us are feeling the bite of high prices on everyday items.

But is it dangerously high? Well, that depends.

After all, height is a relative measure and not a binary one, so how high or low the rate we perceive the rate to be depends on what we’re comparing it to.

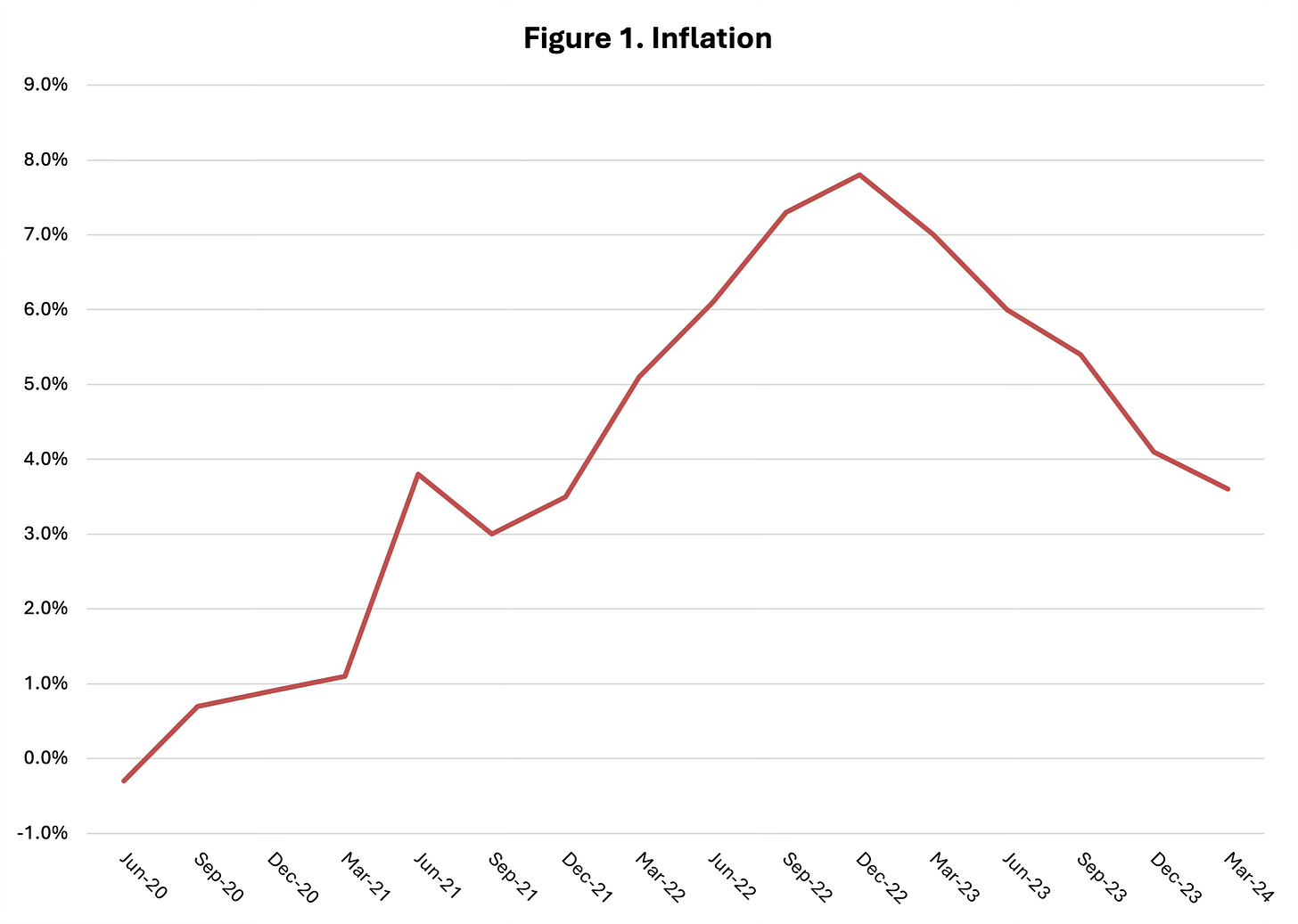

In most articles, a graph like this is used to show us how dangerously high inflation is.

Scary, right? It’s gone from a negative number to almost 8% in two years, which looks huge. However, this argument suffers from two mistakes a temporal fallacy and a selective fallacy.

The temporal aspect refers to the timescale we’re measuring; the data presented here is incredibly high, given the time period we’re covering. However, when viewed in a different time period, we are able to see the same data in a different light.

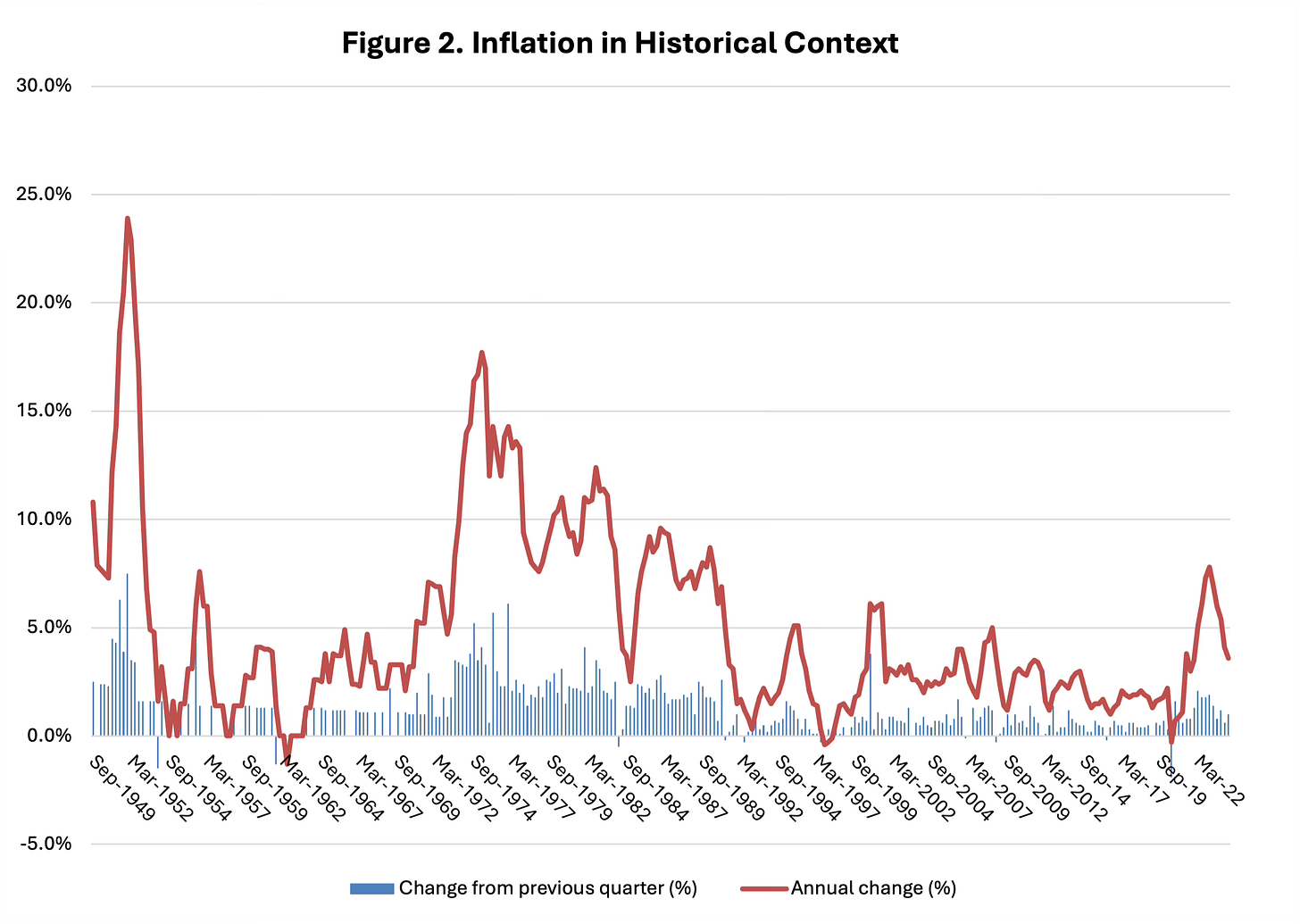

When we extend the data back 100 years, we start to see a different picture of what’s happening. Is this the highest inflation we’ve seen in awhile? Yes, it hasn’t risen above 5% since the turn of the millenium.

Is it the highest it’s ever been? Not even by a long shot. As we can see the immediate aftermath of the Second World War wreaked havoc on inflation, seeing an annual change of nearly 25%. Similarly, the oil crisis of the 1970s drove prices north of 10% and took nearly 20 years to return below 5%.

Is it even the highest inflation has been even in my lifetime (just shy of 40 years)? No. Throughout most of the Hawke, Keating, and Howard years, inflation fluctuated between 3-5%.

Economists (myself included) rely on data to measure what is happening within a particular area of economic activity, whether that’s a company, an industry or a state. While the old adage that ‘the numbers don’t lie’ holds true in most cases, the unfortunate reality is that economists do.

Now, I don’t mean to insinuate that all of us in the economic profession are liars (although I’m not, not insinuating that either), rather I just want to highlight that we’re all guilty of lies of omission when it comes to the numbers.

Crucially, the context that we present data in changes how people perceive it. This is the selective fallacy I alluded to early, we pick and choose not only which data to present, but also how and in what context we present it.

In the case of the inflation story, most coverage is highlighting that it is the highest it’s ever been, but either don’t mention or skim past the fact that it has fallen every quarter since December 2022 and is now half what of what it was at the peak.

While none of this additional understanding changes our experience of inflation, it can have critical impacts on the way we respond to it, both as individual consumers and as a market economy more broadly.

Increased Demand Will Increase Inflation

Now, this second step in the logic chain is where it gets a little more complex. I’ll give the commentators who I am criticising some credit, as it is true that increasing demand can increase inflation…but it depends on what type of inflation we’re talking about. This is the introductory, first year, ECON101 stuff that is bothering me so deeply at the moment.

The coverage has been universal in a treatment of inflation as a singular, homogenous phenomenon. Unfortunately, that’s not remotely true, either in theory or practice.

Indeed, there are three broad economic phenomena that we describe collectively as ‘inflation'.

First, there’s a demand-pull, where the demand for goods and services is greater than the supply, which occurs when people’s capacity to pay for things increases, usually in the form of higher wages.

Basically, when how much stuff there is doesn’t change, but our capacity to pay for it increases, businesses increase prices to ensure that there isn’t a run on their products (and to increase profits).

For example, if average wages are growing, and your wage went up by $50 a week, then your electric company might bumping the price they charge by $20 a month, because they know that even if you don’t sign on for another year there’s a pretty good chance someone else will be happy to pay the rate they’re charging.

However, there’s also a cost-push, where supply falls below the level of demand. This is what happened in the 1970s, when oil became scarce and all byproducts (crucially, plastics and petrol) became much more expensive as a result.

Put simply, when we want stuff and have the money to pay for it, but there isn’t enough of the stuff to go around, prices tend to increase. This happens because businesses are selling fewer goods, so need to increase the prices to offset their loss in production; because selling 4 sets of headphones for $250 each will net you the same revenue as 8 at $125.

Finally, and most crucially, there’s inflation expectations. This is pretty much exactly what it sounds like, because when firms and household believe that prices are going up, they start pre-emptively acting like they’re going up.

This is where context becomes important, because if we as consumers think that inflation is high, we reduce our consumption and actually restrict demand, leading to a cost pull, where companies raise prices to account for the artificial drop in demand.

After all, if people are only buying 6 sets of your $125 headphones ($750 revenue), then you’re better off selling 4 pairs for $250 ($1,000 revenue).

Now, all the coverage is treating inflation as a demand push, and as a result saying that anything which increases wages will lead to higher inflation - but is that true?

If so, wages would have been substantially increasing over the past two years.

Unfortunately, not only is that demonstrably false, the opposite is closer to the truth.

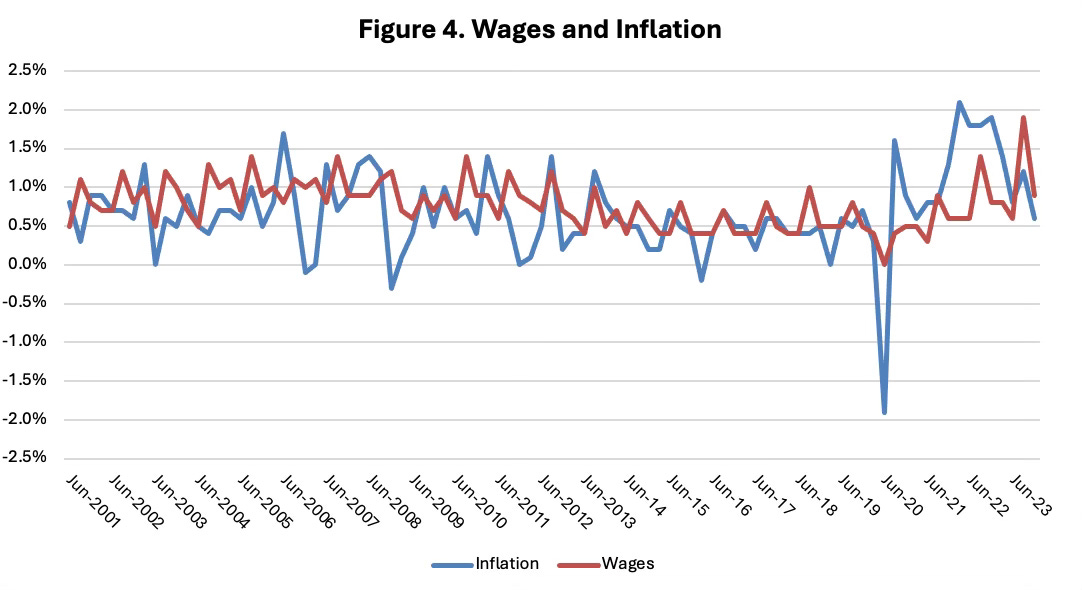

When we look at the relationship between wages and inflation, the picture isn’t so clear cut. They clearly follow each other, and economically they are ‘dependent'; you can’t have inflation without wages.

However, that’s like saying you can’t have a bushfire without oxygen. Sure, their interaction can lead to problems, but there are other things involved in the equation - and if you reduced it too much or got rid of it we’d have a much bigger problem.

Crucially, wages aren’t the only thing that influences inflation; there’s also profits. Profits matter to inflation because if prices are going up, but wages are relatively stagnant, that means that the prices are artificially inflated - they’re higher than they need to be to generate a normal amount of profit, and are being used to drive greater and greater profits.

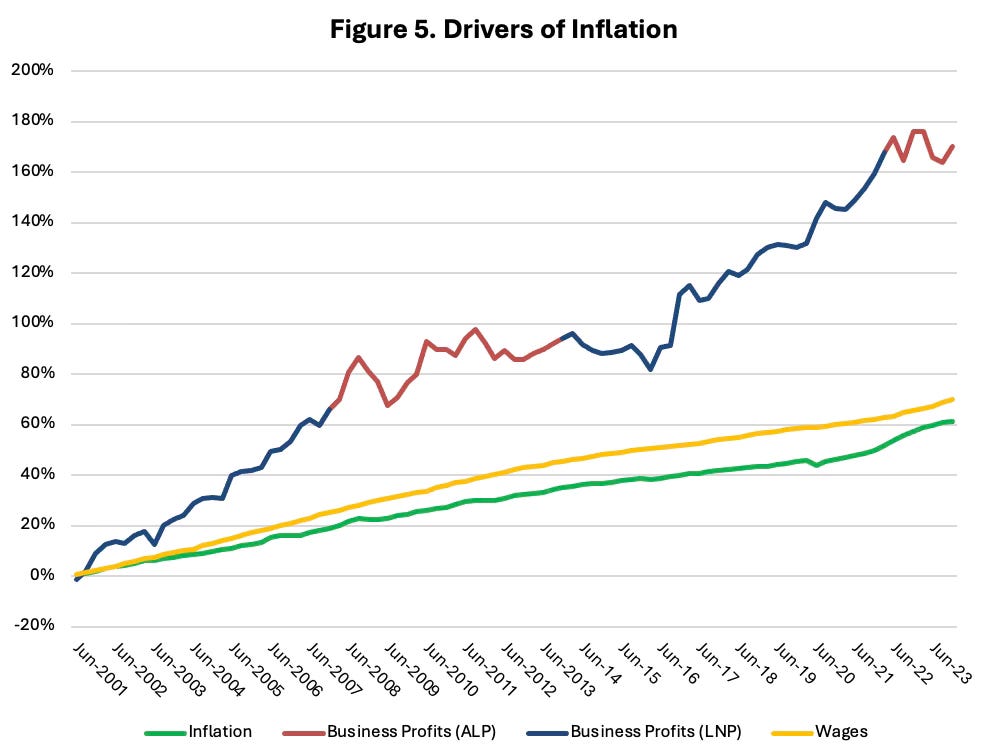

When we look at the cumulative changes to prices (CPI), wages (WPI) and profits (there’s not acronym, just more profit), we start to get a clear picture of what’s actually happening in the economy.

There’s no doubt that wages have grown at a faster rate than inflation since around 2004 - but that’s not the most important story contained within the graph.

Profits have grown at a near exponential rate over the last couple of decades, increasing by nearly 175% between 2001 and 2023. Over the intervening period, wages only grew by 70% over the same period.

This isn’t just an economic problem, but a political one.

I’ve highlighted the graph to show the political difference in profits. When Labor are in power, profits start to moderate and grow at a similar rate to wages, but when the Coalition enter office, profits become supercharged.

This often goes unreported, for fear of the appearance of partisanship amongst commentators, but to call back to the familiar adage from a previous passage, the numbers don’t lie.

While profits growing isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it has always been predicated on their correlation with wages - what’s good for the goose is good for the gander.

Except as we can see from the data, profits have been decoupled from wages, meaning their correlation has been shattered along with the social contract that sustains them.

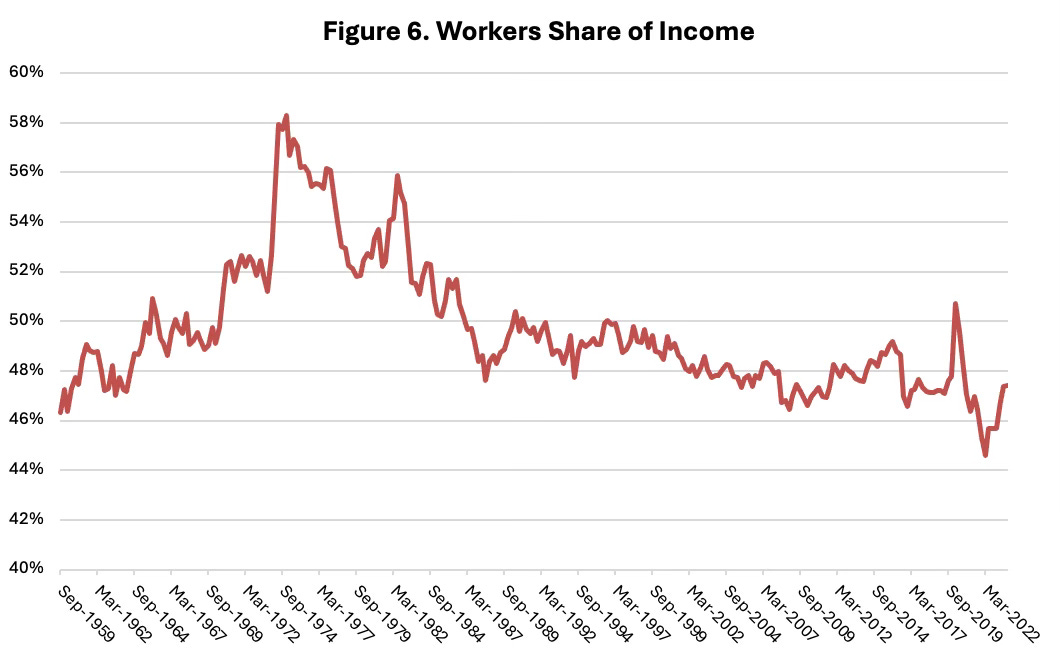

Indeed, we can see that while profits have grown considerably, the 'share of the pie' that workers are getting has fallen substantially, and by this measure workers today are no better off than they were in the 1950s.

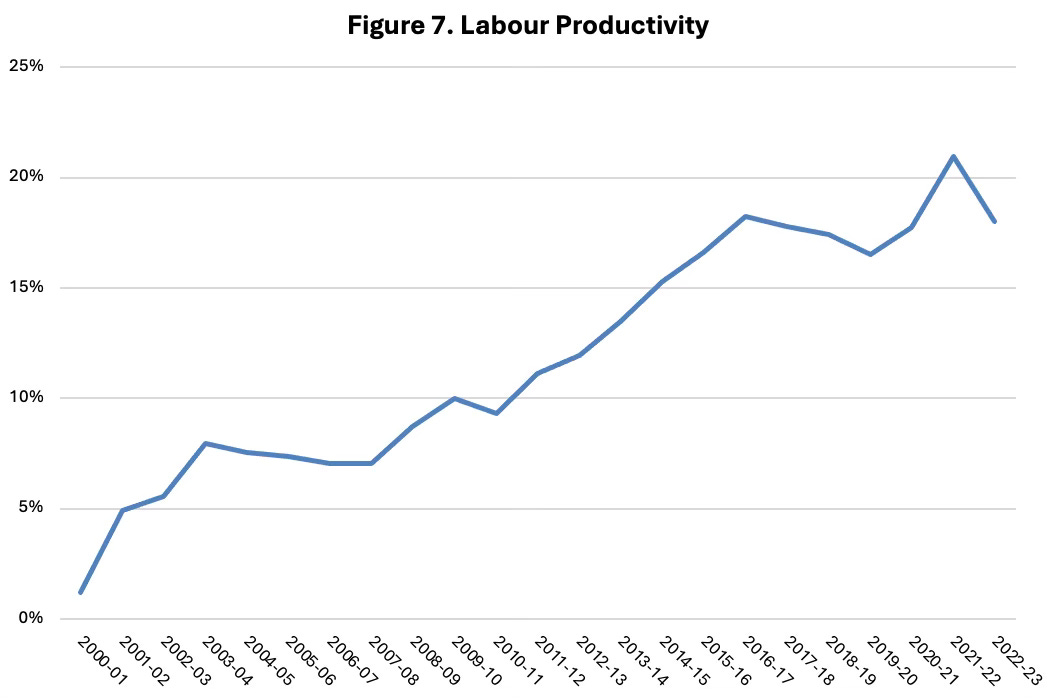

Many call for an increase in productivity to get wages moving again, saying that if workers were more productive, employers could afford to pay higher wages.

Unfortunately, the data is clear on productivity as well.

Labour productivity has been growing steadily over the same time period, increasing by 20% over the last 22 years. Workers have held up their end of the bargain and they’ve been burned for it.

Fiscal Restraint Is Needed To Curb Inflation

At best, a focus on wages and spending is an incomplete understanding of the situation. At worst, it’s actually encouraging solutions that will make the situation worse.

When people arguing against income support during the current inflationary crisis, they say that we can’t spend more because it will be 'pouring fuel on the fire’.

However, what they’re not telling us is that we’re not doing anything that will actually put the fire out either, and that by focusing on wages and ignoring profits, we’re letting the winds of corporate greed fan the flames.

Unfortunately, almost all mainstream commentators (not to mention most politicians and public servants) have only been taught one school of economics, and when all you have is a hammer, everything you see is a nail.

Cutting services, reducing public expenditure, and exercising wage restraint might not be throwing fuel on the fire, but it’s not the kind of hose we need to put it out either.

As we can see from the above analysis, the problems we keep highlighting and the solutions we propose to fix them are incorrect, inadequate and incapable of providing relief for Australia.

We need to start invest in solutions that target our actual problems.

The structural reforms that the government is investing in, through it’s Future Made In Australia program are a good start, as they diversify the economy which create economic activity, new jobs and open new avenues for productive investment that grow the economy as a whole, without growing inflation.

However, if we don’t tackle Australia’s noted problems surrounding economic and corporate dynamism, market concentration and anti-competitive behaviour, not only will inflation continue to plague us, we will continue falling behind the rest of the most innovative and resilient market economies.

The Albanese Government has held essential inquiries into economic dynamism and supermarket price gouging, both of which have unearthed a plethora of data to demonstrate the problems I’ve highlighted here.

Unfortunately, the solutions that they are proposing to implement in response have been tepid at best, and at worst will do very little to solve the problems.

If he's serious about tackling inflation, then he would do well to draw inspiration not from Paul Keating, but from another mythic figure who knew how to turn a phrase and make the hard decisions:

Theodore Roosevelt.

What Would Theodore Roosevelt Do?

This article has already gone on far too long for me to extol all the reasons why Theodore Roosevelt was the greatest president America has ever known (indeed that would be another whole article), but behind all the bravado and buffalo wrestling, lay his commitment to protecting working people from the dangers of monopolisation, market concentration and managerial greed.

As a highly educated member of the landed gentry with familial wealth going back to colonisation, you could hardly call Roosevelt a socialist or a reactionary populist. However, he advanced the causes of labour and environment at a time when his party supported neither.

Crucially, the Square Deal policy agenda he designed at the dawn of the 20th century pursued the “three C’s” that would come to define his presidency and radically reshape America for the better: Conservation, Corporate Law Reform, and Consumer Protection.

While conservation is equally important in the current context, it’s real commitment to the latter two that we desperately need in Australia now.

Much like the Albanese Government, Roosevelt’s presidency encountered an incredibly powerful cabal of corporate interests, and the majority of his contemporaries warned him that taking the fight to them would be political suicide.

However, Roosevelt had the fortitude to stare them down and passed laws which forced greater transparency in business dealings with suppliers and consumers; he created powerful new public authorities tasked with regulating, prosecuting and punishing corporations who acted outside the national interest; and reduced the regulations on trade unions which hampered their industrial activities.

Most importantly, successfully brought 44 anti-trust suits to trial leading to the breaking up of dangerous monopolies in transport and energy, and implemented price controls on essential goods and services when corporate greed drove them too high.

As a result, his face is carved into the side of a mountain for eternity, while his detractors names are lost to sands of time. Because then, just as now, the people were crying out for someone to help them.

If we’re serious about tackling inflation, then we need to be clear about what is driving it, and what it will take to accomplish. I’ve used the ‘numbers don’t lie’ adage a number of times in this article, but that’s not the one that I would want to communicate to the Treasure or the handful of people who will actually read this.

I’ll leave you with the timeless words of America’s 26th President, the man with his face on a mountain, who coined a turn of phrase which I think is powerful wisdom for the situation we find ourselves in today:

"It is hard to fail - but it is worse never to have tried to succeed"

Theodore Roosevelt, ‘The Strenuous Life’, 1899

Dear Shirley,

This is superb. Lucid, rational and full of well-digested economic wisdom.

Janet McC

Great to finally see you posting on here, Shirley. You have been missed!